Welcome to Daily Conquest! Events are in the saddle and it’s time to zoom in on parts of the Constitution that rarely get a look — the presidential disability provisions of the 25th Amendment.

Photo by Luke Stackpoole on Unsplash

Is the Twenty-Fifth Amendment now in play?

Ratified on February 10, 1967, the Twenty-Fifth Amendment was adopted to resolve issues of presidential succession and disability on which the Constitution was silent or for which previous provisions were considered inadequate to the nation’s needs.

The amendment has four sections. Section 4 deals with situations in which the president is unable to discharge the powers and duties of office, but can’t or won’t step aside.

President Biden withdrew from the 2024 presidential race due to his significant cognitive issues. As of today, it appears he intends to serve out the remainder of his term, while endorsing Vice President Harris to succeed him as the Democrat nominee. However, if his cognitive issues are sufficiently serious as to warrant him not running for re-election, is he able to discharge the duties of office?

The Speaker of the House and other Republican officials don’t think so and have called for Biden to resign. Perhaps he will. But if he doesn’t, what recourse do those who believe he cannot carry out his duties have for removing him?

One route for removing a president is impeachment. However, the Impeachment Clause reserves impeachment for “Treason, Bribery, or other High Crimes and Misdemeanors”. Merely being unable to carry out the duties of office, as opposed to having committed a crime, is not a proper basis for impeachment.

In fact, this gap in constitutional tools for dealing with such a situation is part of what led to the Twenty-Fifth Amendment’s adoption.

Whenever the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall immediately assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President…

Twenty-Fifth Amendment, Section 4 (in part)

The stop and go amendment

A discussion of the history, drafting, and ratification of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment can wait until another day.1 Today we’ll stick to outlining the process by which a president unable to carry out his duties can be removed.

As the excerpt above shows, the first step requires action by the vice president and “a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide.”

At present, Congress has not by law provided for any other body to be involved, so we’re left with the vice president and principal officers. Which, right away, starts raising questions of just who this group comprises. But before we get to that, let’s take a look at the steps of the process itself.

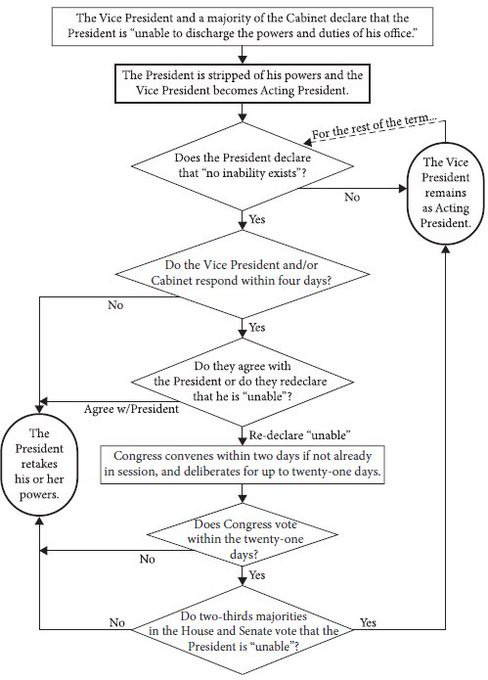

Just look at this chart:

25th Amendment Section 4 Flowchart (Created by Brian C Kalt)

What could be simpler, right?

This is one clunky amendment. But it’s what we’ve got.

The process potentially involves the president, vice president, members of the Cabinet2, and both houses of Congress.

If the president at any point agrees to step aside, matters can be resolved right then — the vice president will become acting president until such time as the president’s inability to carry out his duties ends.

If every participant digs in his or her heels and takes the full time allotted for each step, it could take most of a month to conclude the process — which could then immediately start all over again!

Does this seem overly complicated to you?

It is complicated.

But whether it is too complicated is debatable. While the Twenty-Fifth Amendment doesn’t enable fully removing a president from office (as the impeachment process does), it can strip a president of his powers of office, which amounts to the same thing.

This is serious business and should not be undertaken lightly. The chief executive is the highest elected official in our system of government. Section 4 empowers the president’s own Cabinet to sideline him against his will. The drafters of the amendment designed this multi-stage process of declarations and counter-declaration as a check on abusing this process.

The final decision, should it go that far, is left to Congress, with a high bar for stripping the president of his powers against his will — two-thirds of both the House and Senate must agree to do so. That is the same level of agreement needed to override a presidential veto.

Presidential vices

The first box in Professor Kalt’s3 helpful chart reads that “a majority of the Cabinet” must agree with the vice president to declare the president unable to perform his duties.

It seems a fair reading that no matter what a majority of the Cabinet thinks, the vice president must be on board to begin the process: “Whenever the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments…”

Do you see what I mean? It’s “the Vice President and a majority”. Not a majority that includes the vice president. But a majority that agrees with the vice president.

The vice president alone can’t start the process without the concurrence of a majority of the Cabinet.

The Cabinet, even if unanimous, can’t start the process without the vice president.

Which means that either the vice president or a majority of the Cabinet could squelch any Section 4 process from the get-go.

This is the first safeguard.

Will the real Cabinet please stand up?

But let’s go back to that majority of the Cabinet. While the chart says “Cabinet” for convenience, it’s really the principal officers of the executive departments who decide.

Is that the same thing as the Cabinet? Not exactly.

So who are the principal officers of the executive departments?

At a minimum, they are heads of the fifteen “Cabinet-level” departments — the secretary of state, secretary of defense, secretary of treasury, attorney general, and so on.

However, President Biden has designated ten other officials as having Cabinet rank:

Additionally, the Cabinet includes the White House Chief of Staff, the US Ambassador to the United Nations, the Director of National Intelligence, and the US Trade Representative, as well as the heads of the Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Management and Budget, Council of Economic Advisers, Office of Science and Technology Policy, and Small Business Administration.

Are they in the Cabinet? Yes.

Are they “principal officers of the executive departments”? Maybe. But probably not.

Debates over the amendment in Congress in 1965 made clear that “principal officers” included ten then-existing Cabinet secretaries, plus the head of new executive departments subsequently established.4

Specifically not intended were “the U.S. Representative to the United Nations; the Secretaries of the Army, Navy, and the Air Force; the Director of the Poverty Program; and the head of the Atomic Energy Commission.”5

By analogy, the ten extra officials President Biden has granted Cabinet rank are not thereby granted the rank of principal officer. So they’re out of the equation.

Sorry, SBA and EPA heads! This meeting is for above the line talent only.

Which means that, to initiate the Section 4 process, at least eight out of the fifteen Cabinet secretaries6 would have to agree with Vice President Harris that President Biden is unable to discharge his duties of office.

But wait! There is one more twist!

The acting secretary problem

There are currently two vacancies in President Biden’s cabinet, the Department of Labor and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. These departments have acting secretaries, who have not been confirmed to those positions by the Senate. Do they get a vote?

Not to prolong the suspense, the Congressional debates seem to support an acting secretary being empowered to take part in the Section 4 disability determination, but it is a point that could be challenged. Still, with only two acting secretaries, a majority of the principal officers could form without needing their votes.

Meanwhile, in Section 3

Section 4 of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment is the process for dealing with a president who may not be able to discharge his duties but can’t or won’t step aside. It is a potentially adversarial and drawn out process.

However, what if President Biden himself determines or agrees that he is unable to carry out his duties? What then?

He could, of course, resign. But short of that, he could invoke Section 3 of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment:

Whenever the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, and until he transmits to them a written declaration to the contrary, such powers and duties shall be discharged by the Vice President as Acting President.

Twenty-Fifth Amendment, Section 3

President Biden could declare himself unable to carry out his duties and the powers and duties of office would transfer to Vice President Harris, serving as Acting President, potentially for the balance of Biden’s term.

Will any of these scenarios happen? Who knows!

But if the Twenty-Fifth Amendment comes into play, I hope this brief overview will help you follow what’s happening.

More to come

We’ll get back to our discussion of freedom of speech soon — and deal with other topics as developments warrant.

If you found this edition informative and useful, please click the heart icon! You can also leave a comment or share Daily Conquest with a friend.

Until we meet again — Conquer the Day!

If you can’t wait, I recommend reading the book The Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Its Complete History and Applications, Third Edition by John D. Feerick.

We’ll come back to this.

Kalt also has a book about the Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Unable: The Law, Politics, and Limits of Section 4 of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, Brian C. Kalt

Feerick, p.117

Ibid.

Just to be thorough, they are “the Secretaries of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, Interior, Labor, State, Transportation, Treasury, and Veterans Affairs, and the Attorney General.” The White House